Without a doubt the invasion of Indo-Pacific lionfish into the marine environment of the western Atlantic is the worst example of an invasive marine species takeover of critical waters in recent history. Most shocking has been the incredible speed with which the lionfish has spread around the Caribbean and entire western Atlantic and established itself in every location and at every depth in the water column. We’ve known for a long time that the start of this invasion most likely began in southeast Florida by a few aquarists who released their pets into the ocean, perhaps good-hearted, but with awful ramifications.

How lionfish spread through the western Atlantic

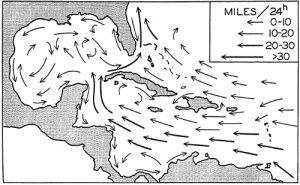

What makes this rapid spread even more surprising is that it goes against the prevailing ocean currents which follow the trade winds across the Atlantic, into the Caribbean, and Northwestward toward Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. Anyone who has seen a lionfish in the wild realizes immediately that this fish is not a strong swimmer. The lionfish is designed to be an ambush hunter on the reef and does not have the size, build, tail design, or strength to swim quickly for long distances or work into a current.

In a recent tagging study of lionfish documented here, lionfish have proven to have ‘high site fidelity’, meaning that many of the tagged lionfish were recaptured in the exact same spot, and some were captured 7 months later and only 200 feet away! So we know that the lionfish did not swim across the Gulfstream nor did they swim southeast to the Caribbean, and the prevailing currents should have swept the eggs away to the northwest into the Gulf of Mexico or up the east coast. So how did the lionfish spread against these prevailing ocean currents?

prevailing ocean currents

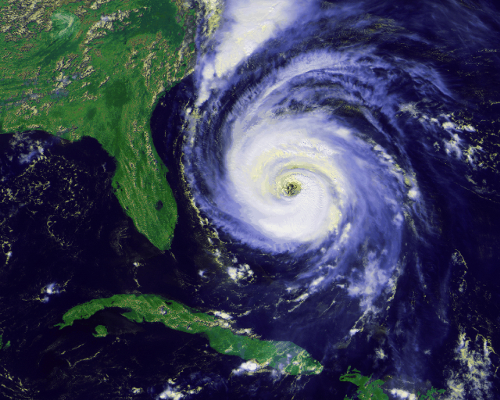

Thanks to a new research paper recently published by Mathew Johnston and Sam Purkis of Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center we now have an answer….Hurricanes. In their study which focused on the spread of lionfish across the Florida Straights to the Bahamas (a journey which should have been prevented by the fast-moving Gulfstream) the authors identify 23 examples of times between 1992 and 2006 in which strong storms had the potential to disrupt the normal current flow and allow the dispersion of lionfish larva to the Bahamas. Through their work they also extrapolated that these storms allowed the lionfish to increase their rate of spread by more than 45% and magnified the population by more than 15%. While the authors’ work focused on the spread between Florida and the Bahamas, it’s logical to conclude that these storm disruptions are also what allowed the further propagation southeastward down the island chain of the Caribbean against those prevailing ocean currents.

This concept of tropical storms disrupting the normal ocean currents to show how lionfish spread gets even more interesting when we combine it with the recently published paper by Alex Fogg et al which looks at the reproduction rates of lionfish in the northern Gulf of Mexico. In this large study they showed that the reproduction rate of lionfish was at its peak from May to December, which just happens to coincide with the peak of hurricane season in the Atlantic. During this warm water period of summer when storms come through and disrupt the normal flow of ocean currents lionfish are also breeding at their peak rate! A double whammy that has only helped the lionfish to be the perfect invader that it is.

Now that we have a better understanding of how lionfish spread what does this mean for the future? While lionfish have been the most successful invasive species, they are by no means the only marine invader in Florida. Warming oceans will continue to increase the frequency of the current-disrupting tropical storms and will help new invasive species to breed and spread throughout the waters of the western Atlantic. We must always be vigilant and immediately remove invasive species when they are spotted and educate people about the dangers of releasing non-native species into the wild.

I think that we should investigate the following hypothesis/mode in which these lion fish, have exploded in population throughout the Caribbean, and in doing my research, did NOT find any documentation, on this subject (Dispersal via the Sargasso Sea and seaweed rafts, which are being broken off during Gulf stream Eddies/Gyres’ or Storms passing through the Sargasso Sea), why I am saying this, is a case in point !!..

A friend of mine who is a commercial fisherman and was also the President of All Guadeloupian Fishermen UMPIG, was about 30 plus miles up into the Atlantic Ocean, trolling for Dolphin/Mahi Mahi, and while there, as he was passing a Sargasso weed raft, and saw a white 5 gallon plastic bucket floating, so he picked it up, and on doing this, discovered 8 baby lion fishes hiding inside..

Also the fact that Barbados, observed lion Fish in their waters, long before Montserrat and the surrounding Leeward islands.

Well in my research the Lion Fishes living in Florida and North Caroline, when they spawn, and seeing as how the lion fish releases/spawns 2 buoyant egg masses, which after they are fertilized, then float to the surface, these eggs and later embryos, in their adhesive mucus sacs, will sometimes get fouled/attached to the floating Sargasso Seaweed, and be transported into the the Sargasso Sea by the Gulf Stream Gyres or Current Eddies etc., (See map below) where they spend a portion of their juvenile life there, preying on the eggs and baby pelagics’ of Eels; flying fishes; dolphins’; tuna’s, etc. and by doing this will also decimate these pelagic species also !.

So not only will we lose our reef fishes, but also our Coral reefs’ too..

The Eddies and Gyres that direct the currents into the Sargasso Sea, transporting these Lion Fish egg masses.

Now storms/rough seas, will also cause Sargasso seaweeds, to break off and be directed down through the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, or across the Atlantic to the Azores; Canary Islands; West Coast of Africa; Central and South America..

Note: The Sargasso Sea Alliance went out to the Sargasso Sea to dive,about 5 years ago, HOWEVER did not find any Lion fish in their area of checking..

Look up :- North Atlantic Gyre on line to see the various Currents that circulate around the Atlantic/Sargasso sea and the entire Atlantic ocean.

Thank You,

Capt. John Howes